A. smithiana by Paul Kroeger

Poisonous and very serious, causes kidney failure.

Toxins: allenic norleucine (aminohexadienoic acid) and chlorocrotylglycine

Symptoms: Time of onset 4 to 11 hours

Nausea, vomiting, possible diarrhea, abdominal pain; possible myalgia; delayed polyuria, oliguria, kidney failure.

Grows rooted deep in the ground near conifer trees in mature forests in late summer

and fall, often solitary. Uncommon, but can sometimes be locally numerous, they are medium sized to large, striking white Amanitas with a tall and robust stature. The stem is usually longer than the cap is wide, but because the base is deeply rooted much of the stem may not be visible above the forest floor. They make white spore prints.

Caps are white or whitish and 6 to 12 cm wide, at the beginning round to convex but opening to broadly convex then becoming flat at maturity. When young and moist the surface is only faintly viscid or slippery and soon becomes dry. The edge of the cap is heavily festooned with white to dirty whitish cottony veil remnants which often hang down like cottony icicles, beneath which the cap edge’s surface is smooth with no trace of radiating lines or grooves corresponding to the gills. The flesh is thick and white and not staining. The odour is mild at first but soon becomes unpleasant, described as decaying protein; slightly ammonia-like or like ham gone bad.

Gills are white to cream, closely spaced or crowded and free from stem or just barely attached to stem apex. The gill edges are often fringed with white crumbles of veil particles.

Stem stout white to whitish, solid but rather soft in texture, 9-18 cm long by 1 to 3 cm wide, slightly tapering upward in upper portion, coated with scaly white remnants of veil and mealy material that will often transfer to the fingers when handled. The partial veil rarely forms an entire ring or annulus but often is observed as a band of ragged patches adhering near the stem’s apex. The base is expanded into a parsnip shaped bulb that usually extends deep in the ground into the mineral soil. The volva is usually present as ragged bands and scales of white wooly crumbly material above the widest point of the stem.

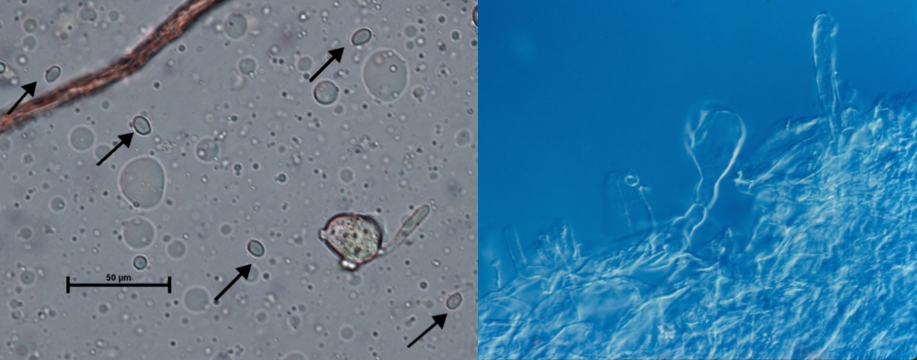

Microscopic: Spores are 10.7-13.3 x 6.8-8.0 microns, broadly elliptic to elongate, smooth, thin-walled and hyaline, amyloid (blue in Melzers iodine solution). Inflated subglobose to broadly elliptic cells of veil tissue adhering to the stem base can help identify this species if cap and gill fragments are not present in a suspect sample of material ingested. Such structures are not found in the Pine Mushroom.

Photomicrographs of A. smithiana. Left: Amyloid spores in soup. Right: Veil cells from base of stipe

This mushroom causes serious but usually non-fatal poisoning when mistaken for the highly desired Pine Mushroom or Tricholoma magnivelare. A distinctive characteristic of the Pine Mushroom that sets it apart is its very strong spicy cinnamon-like smell, very different from the rather offensive odour of Amanita smithiana.

The Pine Mushroom lacks the white crumbly or powdery and easily rubbed off veil coating the stem and cap edge of A. smithiana; and has a very tough cartilaginous stem which can resist being squeezed, or pushed on the side with the thumb (a test applied to Pine Mushroom stems by experienced pickers to test for insect damage). In contrast an A. smithiana stem will crush easily with such treatment.

Another test which can help distinguish one from the other is to observe the form after leaving mushrooms on their sides for several hours or overnight. All Amanita species are strongly geotropic, meaning that the stem will bend trying to orient the cap and gills horizontal to the ground. This does not occur in Pine Mushrooms.

Poisonings by Amanita smithiana have occurred when a person familiar with Pine Mushrooms has gathered one or more of them amongst genuine Pine Mushrooms; the two species can grow side by side. Pine Mushroom stems arise from a grey ashy layer between the humus and the mineral soil, and the entire base can usually be extracted intact with a gentle rocking and twisting motion. By contrast, A. smithiana is rooted deep in the lower mineral soil and the base is usually broken away unless excavated carefully.

Amanita smithiana has become a frequent cause of very serious mushroom poisoning in British Columbia. Here is a sample of cases where this dangerous mushroom was apparently mistaken for Pine Mushrooms:

In October of 1994 a 31 year-old female was poisoned after eating 6 mushrooms gathered near Sechelt as Pine Mushrooms. It was noted that one mushroom seemed different from the others. Eight hours after eating them she developed nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain. She vomited frequently for 7 days and diarrhea persisted with evidence of blood in both vomitus and stool. She experienced significant fatigue and generalized body pain. Urine output had begun to decrease 4 days after ingestion. She presented at the emergency department 6 days post-ingestion in some distress, moaning and retching. She was hospitalised and received hemodialysis on the first and third day, urine production resumed after 3 days in care and she was discharged 11 days after admission or 17 days post-ingestion.

In November of 1994 a 49 year-old male was admitted to hospital in kidney failure five days after eating “Pine Mushrooms” he had picked near Boston Bar. Six hours after eating the mushrooms he experienced mild symptoms of indigestion, nine hours after the meal he became nauseated and began to vomit. Vomiting continued through that night and was intermittent for five days. Neither blood nor bile was evident in the vomitus. He did not have diarrhea, abdominal pain, chills or fever. He presented at the emergency ward because of increasing nausea and weakness, and high creatinine levels and other lab findings indicated kidney failure. He received hemodialysis on the first day of treatment then on alternating days for a total of 4 sessions. He was in hospital for 9 days then followed as an outpatient. Creatinine levels gradually dropped over 37 days post-ingestion and kidney function gradually normalized.

In October of 1995 two adult males ate four “Pine Mushrooms” harvested near Nanaimo by cutting the stems at ground level. Five hours later the older 64 year-old man developed nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and excessive urination (polyuria) but did not have diarrhea. The younger man remained asymptomatic. Two days after ingestion the ill man’s urine production ceased and two days after that he visited his physician because of back pain. He was anorexic and very weak and found to have an elevated creatinine level. He was admitted to hospital in acute kidney failure. He received hemodialysis treatment every 2 or 3 days for 5 weeks. During his hospital stay he experienced continuing nausea and dyspepsia. Urine production slowly improved and he was discharged after 30 days with dialysis continued as an outpatient until 40 days post-ingestion. When the bases of the mushrooms were excavated by the younger man after illness developed, they were found to be from two A. smithiana growing next to two Pine Mushrooms.

In November of 1995 a 73 year-old diabetic male ate one large cooked mushroom he had picked near Nanaimo. Five hours later he developed nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, frequent urination, diarrhea, dizziness sweating and blurred vision and these symptoms persisted overnight. He presented at hospital the next day with signs of kidney failure and was transferred to a dialysis centre. Urine production had ceased and dialysis was begun the next day and repeated three times a week for 4 ½ weeks. Symptoms of nausea, vomiting and intermittent abdominal discomfort persisted. Creatinine levels peaked after 10 hospital days then decreased steadily, urination also resumed on the 10th day and slowly increased. He was discharged 5 weeks post-ingestion.

In October of 2011 a 63 year old male consumed soup made from several wild mushrooms gathered on one of the Gulf Islands. He identified the mushrooms as Puffballs (Lycoperdon perlatum), Meadow mushrooms (Agaricus campestris), the Prince (Agaricus augustus) and Pine Mushrooms (Tricholoma magnivelare). The mushrooms were boiled in water then onions, garlic and cream were added. Four hours after eating the soup the patient became ill, and twenty hours after ingestion kidney failure became evident. The patient was hospitalized for two weeks and received dialysis over nine days. Unconsumed portion of the soup was submitted for identification: Amanita smithiana had been mistaken for Pine Mushroom.

In October of 2016 an adult male picked and ate a large amount of what he thought were Pine Mushrooms collected near Nanaimo. After seven hours he developed vomiting and diarrhea and was admitted to hospital where he experienced kidney failure and required hemodialysis for several days.

A. smithiana collected as Pine Mushrooms near Nanaimo, photo by patient’s wife.

Bibliography

Ammirati, Joseph F. 1985. Poisonous Mushrooms of the Northern United States and Canada. University of Minnesota Press

Apperley, S., P. Kroeger, M. Kirchmair, M. Kiaii, D. T. Holmes, and I. Garber 2013 Laboratory confirmation of Amanita smithiana mushroom poisoning. Clinical Toxicology 51, 249–251

Arora, David 1986 Mushrooms Demystified. Ten Speed Press. Berkeley CA

Arora, David 1991 All that the Rain Promises and More… Ten Speed Press. Berkeley CA

Bas, C. 1969 Morphology and Subdivision of Amanita and a Monograph on its Section Lepidella. Persoonia 5 (4) pp. 285-579

Benjamin, Denis R. 1995. Mushrooms: Poisons and Panaceas. A Handbook for Naturalists, Mycologists and Physicians. W.H.Freeman and Company

Chilton W.S., Tsou, G., De Cato, L. Jr, Malone M.H. 1973 The unsaturated norleucines of Amanita solitaria, chemical and pharmacological studies. Lloydia 36 : 169 – 173

Jenkins, David T. 1986 Amanita of North America. Mad River Press Eureka CA

Kent, Debra R. and Gillian Willis editors. 1997 Poison Management Manual. The BC Drug and Poison Information Centre Vancouver

Leathem, Anne 1994 Renal failure due to mushroom poisoning. B.C. Health and Disease Surveillance 3 (12) pp. 128-130

Leathem A. M., Purssell R. A., .Chan, V.R. & Kroeger, P.D. 1997 Renal failure caused by mushroom poisoning. J Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 35: 67–75.

Sept, J. Duane 2006 Common Mushrooms of the Northwest. Calypso Press.

Siegel, Noah and Christian Schwarz 2016 Mushrooms of the Redwood Coast: A comprehensive guide to the fungi of Coastal Northern California. Ten Speed Press, New York

Trudell, S. and J. Ammirati 2009 Mushrooms of the Pacific Northwest. Timber Press.

Tulloss, R.E. & Lindgren J.E. 1992 Amanita smithiana – taxonomy, distribution,

and poisonings. Mycotaxon 45 : 373 – 387

Turner, Nancy J. and Patrick von Aderkas. 2009 The North American Guide to Common Poisonous Plants and Mushrooms. Timber Press

Warden, C.R. & Benjamin, D.R. 1998 Acute renal failure associated with suspected Amanita smithiana mushroom ingestions: a case series. Acad. Emerg. Med. 5 : 808 – 812.